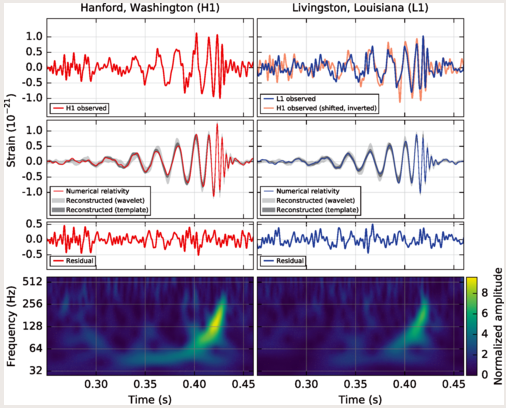

One of the most unique things about physics discourse is the presentation of information. We never present long arrays of numerical data to make a point. We instead use a series of pictures to make that point more clearly. If you take a look at the Evidence/Proof page on this site, you can see that the theory was proven because the data points and associated uncertainties lie along the theoretically-predicted curve. This type of information, the pictorial type, is surprisingly powerful. If you take a look at discourse in advertising, for example, you’ll quickly learn that the information isn’t concentrated into a few pictures or words. Instead, you find that each word carries a similar amount of information, and that in order to properly understand the argument being made you’ll have to read the article from the beginning, word-for-word. But if you look at a typical physics journal article, you’ll find that all the important information is contained in a brief introduction so you know what’s being tested, and a few graphs illustrating the data analysis. For example, take a look at this article from the American Physical Society: APS, we see that all of the data, theory, and conclusion is contained in this image:

Just like the screenshot taken for the Evidence/Proof page, we have predicted curves plotted with observations. The observations fit the theory, and we therefore see the confirmation of a theory. If you read the abstract so you know what’s being tested/measured, and then hop right to this picture, you’ll know all the important information contained in the article. Another interesting rhetorical tool for these images in physics publications is edification or clarification. The only other image appearing in this article is for that purpose:

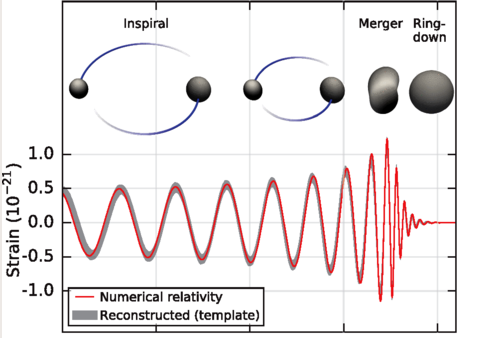

The purpose of this image is to show what’s going on: we have two black holes spiraling in toward each other, until they combine and emit a powerful gravitational wave. This use of pictures in physics discourse is essential to efficient communication, and has been a convention since the first physics publications. Here’s an example from Isaac Newton’s Principia, published in 1687, widely regarded as the birth of physics:

So we can see that this use of pictures is a convention and a tradition that has existed since the very beginning of physics.

If an institution is capable of presenting accessible information like this, then they are more likely to be published, which, as I’ve pointed out here, is a fundamental requirement for the livelihood of an institution. It is perhaps in this one area of physics rhetoric that an institution does not need massive funding. It is for this reason that individuals can excel if they are good at what they do! Look at that picture of Newton’s Principia. Newton was alone in all that work he did. He did not perform expensive experiments, he just used his brilliant mind to produce powerful information in the form of theories. In today’s physics ecosystem, the need for theorists is increasing. Each new experimental discovery calls for a new theory to explain it. We opened up several Pandora’s boxes in the last few years of astrophysics (dark energy/matter). If an institution selects the right individuals — those capable of producing dense, accessible information in the form of physical theories — then they become a more viable institution on the road to expert status.

It is in this area of information production — theoretical physics — that physics communities catch a break from problems due to funding. When the ecosystem sees abrupt progress in theory, e.g. Einstein and Newton, it has opportunity to flourish. When the world is awestruck with the utility of physics it pours money into the physics community. NASA, as you might guess, received most of its funding during the era of the first moon landing:

(wikipedia)

(wikipedia)

The community is like a living organism that needs information to thrive.